By: Eagle Sarmont

As told to Suheer Baig by Eagle Sarmont

I was flying 20 feet over a grass-covered pasture, weaving around the occasional tree and cow. When I came to a road, I’d pull up into a steep climb to hop over it and the power lines running alongside, then dive back down to 15-20 feet to continue my flight. Flying in ground effect like this made my plane feel supercharged. The thrill was so intense it heightened my senses to a degree I’d never experienced—I was hyperaware of everything, both directly ahead and out to the limits of my peripheral vision.

Every wildflower. Every fence post. The dew on the grass. The birds rushing to get out of my way as I roared across the countryside. The emerald-green color of the spring grass, the riot of wildflower colors, even the freshness of the air—I felt and saw them all.

Most amazing of all, my mind was calm.

All the ongoing plans I’d been incessantly chewing on—how to end the doctors and former managers who had effectively killed my wife by not doing their jobs—had stopped. Not because I’d found peace, but because the flying demanded all my attention. For the duration of this flight, the anger and murderous rage that had been eating me up was gone.

The Breaking Point

My wife Claudine died in 2003 after a 30-year marriage and a brutal fight with cancer. The doctors at her last clinic had not been reviewing her test results themselves—they’d left it to the technicians. By the time anyone noticed, she’d gone from cancer-free to stage four. I’ve wondered many times how many years they stole from her.

After she passed, I wanted to end them. All of them.

But Claudine started speaking to me from the other side almost immediately. So even though she was physically gone, I was absolutely clear that she was not dead. I had also been told “Don’t” when it came to my plans. A voice—real, unmistakable, delivered like hardened steel—made it very clear that dealing with these people was not my job and that no one gets away with anything on the other side.

Yet the rage was still there, and I was struggling to find an outlet for it that didn’t involve doing some profoundly serious harm.

This flight made it clear I’d found my outlet.

It was time to disappear. To follow my nose and heart and just fly. No destination, just me and the sky. Ground-effect flying, cloud flying, a road trip with wings. Time to become a ghost—no more stupid people playing stupid games, just me out in the country by myself. Me, myself, and I with a single-seat ultralight and the big blue sky.

An Unusual Therapy

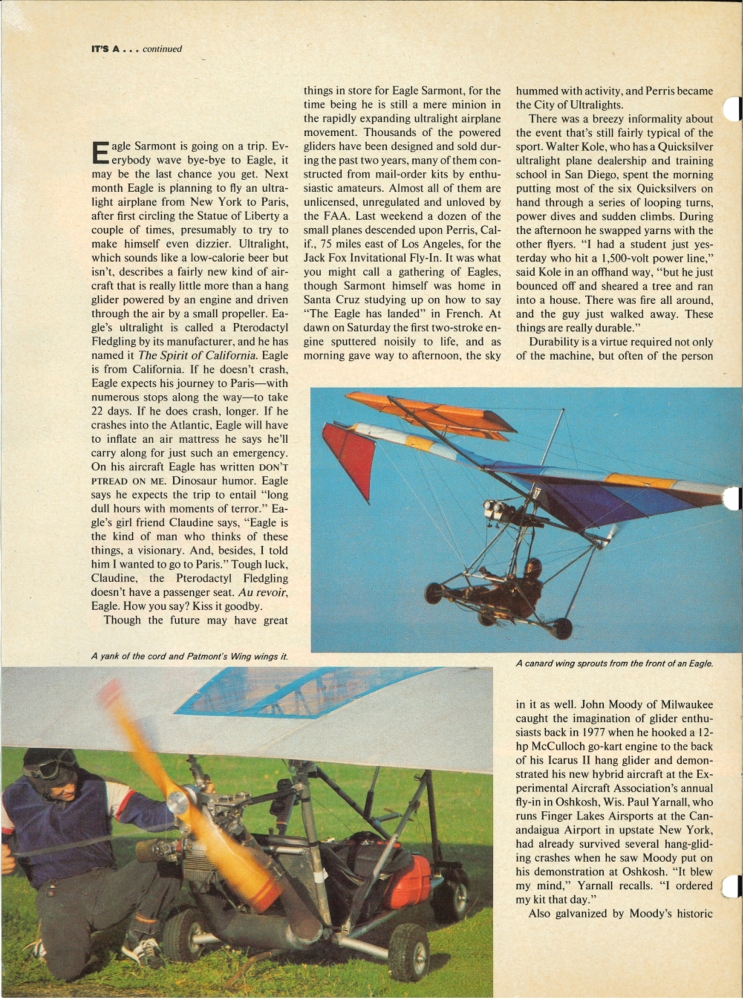

I’d been around airplanes for a long time: light planes, hang gliders, ultralights, sailplanes, homebuilts. My favorites are open-cockpit aerial motorcycles, the kind where you’re totally out in the open—a flying lawn chair on the edge of eternity. When Claudine came down with cancer, I had to let it all go. No time, no energy, no point.

But a few months after she died, I remembered: flying was the last time I’d felt anything resembling joy.

So I bought an ultralight. Not to design or build something new—I just wanted to fly. I bought the most reliable engine I could find, loaded it with minimal camping gear, and took off from a small airport north of LA with no destination in mind.

I told no one. I didn’t file flight plans. I became a ghost.

Flying as Forced Meditation

Here’s what most people don’t understand about flying an ultralight at 20 feet above the ground: you can’t think about anything else. When you’re skimming that low at 55 miles per hour, there’s no mental bandwidth for grief or rage or revenge fantasies. There’s only: wind direction, engine temperature, the ridge coming up fast, where to land if something goes wrong.

It’s forced meditation. The kind you can’t cheat at.

I flew out of California heading east, following roads at first, then just following my nose. I’d take off at sunrise, fly for four hours, land at some abandoned airstrip or country gas station, sleep under the stars or next to my plane on grass-covered fields, and do it again. Kansas.

Monument Valley. The Missouri River.

The flying itself became a kind of therapy I couldn’t have found in any Los Angeles therapist’s office—and I’d tried the conventional route. Therapy asked me to sit still with my feelings.

Flying demanded I forget my feelings entirely or crash.

Some days I’d fly high—over a mile up, what I called “lawn chair on the edge of eternity” altitude, where you’re basically sitting in the sky with nothing in front of you but your feet on the rudder pedals. At that height, you see the curvature of the earth. Your problems look very small.

Other days I’d fly low in terrain-smoothing flight—50 feet over the high points, 300 feet over the valleys, the world blurring past in greens and browns and the occasional startled bird.

Both kinds of flying did the same thing: silenced the voice in my head planning violence.

What the Sky Taught Me

I flew for months. Across the entire country and eventually to Europe. I met people along the way—some of them helped me remember what human connection felt like. Claudine continued to speak to me, showing me things on the other side, helping me understand that while I had every right to be angry, acting on that anger wasn’t my path.

When I finally came back to California, I wasn’t fixed. The grief was still there. But the rage had mostly burned itself out, replaced by something quieter and, honestly, easier to live with.

I landed at the same small airport north of LA where I’d started and walked back into my regular life.

The Choice Life Gives Us

I still think about Claudine every day. I still get angry sometimes at the doctors, at the circumstances, at all of it.

But I also know this: life is designed to be challenging. That’s not cruelty—it’s design. The challenges force us to grow, to choose between living in the world of anger, hate, and fear, or living in the world of love, joy, and happiness.

For months after Claudine died, I lived in the world of anger and fear. The rage was so consuming I was genuinely dangerous—to myself, to others, to any chance of a future that looked different from the past.

Flying gave me something I desperately needed: a way to interrupt that rage long enough that something else could start to grow. Not peace, exactly. Not forgiveness, not at first. Just… space. Enough space that I could start to see I had a choice.

I could stay in the rage, or I could choose something else.

Six Months Later

I’m 74 now. My health is fine—I’m very capable of flying for as long as I want, though I much prefer grass-covered airstrips to pavement these days, both for landing and for sleeping next to my plane.

I still fly, though not the way I did during those months of disappearing. These days when I’m sitting in traffic on the 101, or hiking in the Santa Monica Mountains, or watching the sunset from Venice Beach, I think about those flights and what they taught me.

The lesson wasn’t about flying. It was about attention.

When you’re 20 feet above the ground moving at highway speeds, you have to be completely present. There’s no room for the stories you’re telling yourself, the grievances you’re nursing, the plans you’re making. There’s only now, and the immediate question of survival.

And in that forced presence, I learned something: the rage was a choice. Not the grief—that was real and unavoidable. But the rage, the violence, the endless planning of revenge—that was something I was choosing to feed.

Flying starved it. Every hour in the air was an hour I wasn’t feeding the rage. And eventually, it got weak enough that I could see around it.

What Comes After

If you’re in that place now—the place where the rage is louder than anything else, where the future looks like a locked room with no exits—I can’t tell you what will work for you. I can only tell you what worked for me.

I needed something that demanded my full attention and offered absolutely no room for the stories I was telling myself. For me, that was an ultralight and the open sky.

For you, it might be something else entirely.

The point isn’t the flying. The point is finding the thing that forces you back into the present moment, into the simple mechanics of staying alive and paying attention.

And then, if you’re lucky and you stay with it long enough, you reach the moment where you’re ready to choose. Not between life and death—between anger and love. Between fear and joy.

Between staying stuck in the story of what was taken from you, or opening to what’s still possible.

It’s when you learn to choose to live in the world of love, joy, and happiness that you become ready to take the next step.

I’m still learning to make that choice. Every day. Some days are easier than others. But at least now I know it’s a choice.

And I know that when the rage starts building again—and it does—I can always take to the sky

Eagle Sarmont is a retired aerospace engineer living in California. He invented several concepts that became foundational to modern spaceflight and is the author of “New York to Paris,” a memoir about flying, loss, and what comes after.

Suheer Baig is a developmental editor and writer who works with authors to shape compelling narratives across business, memoir, feature journalism, and fiction.